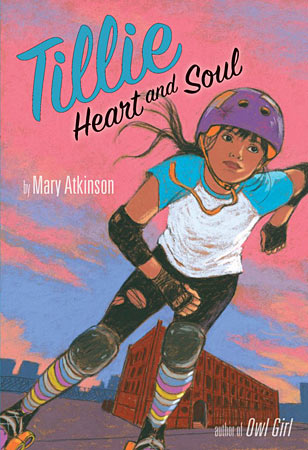

Ten-year-old Tillie practices roller skating wherever she can—even in the old Franklin Piano Factory where she lives with her guardian Uncle Fred. She has to be in the Skate-a-thon with her friends. Surely Mama wouldn’t miss it! But skating in the city is tough, three-way friendships are tricky, and the stupid rules in Mama’s rehab program could mess up all her plans.

Ten-year-old Tillie practices roller skating wherever she can—even in the old Franklin Piano Factory where she lives with her guardian Uncle Fred. She has to be in the Skate-a-thon with her friends. Surely Mama wouldn’t miss it! But skating in the city is tough, three-way friendships are tricky, and the stupid rules in Mama’s rehab program could mess up all her plans.

Will Tillie get to be in the Skate-a-thon? Will she lose her best friend for trying? Will Mama come home to see her?

- A great read for ages 8-12.

- $14.95 • 114 pp

- Order from Amazon

- Order from Maine Authors Publishing

Read the first chapter: Too Much Commotion!

Reviews

Kirkus Starred Review

“An outstanding tale that approaches issues of self-doubt, rejection, and acceptance with sensitivity, warmth, and an engagingly realistic voice”

Read the Kirkus review

Publishers Weekly Review

“Atkinson excels at exploring the girls’ shifting friendship dynamics and the difficulty of managing expectations when it comes to an unreliable loved one.”

Read the Publishers Weekly Review

The Pirate Tree Review

“Mary Atkinson’s second middle grade novel … is a hidden gem.”

Read the Pirate Tree review

Awards

- Kirkus Best of 2017

- Moonbeam Gold Award for Pre-teen General Fiction

Podcast

Listen to a podcast about Tillie with Deb Gonzales on the Debcast

Chapter 1: Too Much Commotion!

Everything’s going really well until Uncle Fred starts yelling at me. I’m rollerblading around his art studio, gliding between worktables, weaving around buckets of paint and rags on the floor, avoiding easels and chairs.

“Tillie!” He signals for me to stop and take out my earbuds.

“What’s the matter?” I ask.

“You’re making too much commotion! How can I get any work done?”

“Um, ignore me?” I say.

“Ignore you, Tillie? How am I supposed to do that?” He turns around from the gigantic painting of bare trees in moonlight he’s been working on. For. Ever. He complains that something’s not right about it. Trees too scraggly? Light too fuzzy? Color too blah?

“Just concentrate,” I say. “Put on your mental blinders. That’s what you always tell me.” I flash him a smile as I skate past the scaffolding he’s set up to reach the high places in his painting.

“Arghh!” He throws his arms into the air in a V. “You don’t have a ten-year-old girl skating around you like a mad hornet when you’re trying to get your work done.”

“This is my work!” I always practice my skate routines in Uncle Fred’s studio. It’s a huge room. Dusty sunlight pours through its tall windows, humongous canvases line whitewashed brick walls, the floor’s the size of a skating rink.

Seriously, it’s big enough for both of us. But Uncle Fred’s been a crab lately, worried that he hasn’t sold any work in a while, annoyed that he’s had to add more hours to his restaurant job.

I skate around his worktable. I’m doing a perfect glide, I’m in the zone, and then…I crash into a plastic bucket filled with paintbrushes, palette knives, and chopsticks. (Don’t ask.) Everything scatters on the floor.

That bucket wasn’t supposed to be there. Tools are supposed to stay on the table.

“Sorreee,” I say. I look up at Uncle Fred, giving him my best droopy-dog face. He looks down at me with that one raised eyebrow thing he does when his patience is about to run out.

“So, um, I should practice in the parking lot?” I ask.

“Yes, TillieBean, I think that would be better for both of us.”

Uncle Fred watches as I get my helmet, elbow pads, and knee pads. I tighten the pads with their Velco straps and put the helmet on my head.

“Let me hear the click,” Uncle Fred says.

I snap the clasp. “Click,” I say.

“Have you got plastic gloves for the trash?” he asks.

Some people think that because my Uncle Fred’s an artist, he’s distracted or absentminded. He’s not. At least not about me. In fact, he could use a little absentmindedness where I’m concerned.

I’m ten years old, and he still hovers over me to make sure I brush my teeth for a full two minutes and tells me to tie my shoes with double knots so I won’t trip.

“Plastic gloves? Right here,” I say, patting the front pocket of my jeans. Like I’d forget. Collecting trash with bare hands? Gross.

“And the trash bag?”

“Yes, Uncle Fred.”

“That’s my girl,” he says.

“That’s my uncle,” I echo.

He knocks me on my helmet with a paintbrush. “Anyone home?”

“Ha, ha,” I say. I roll my eyes at him and then skate out the door, down the long hallway to the freight elevator. Uncle Fred and I live in the old Franklin Piano Factory, a brick building down by the train tracks in the small city of Haversack, Massachusetts.

Long ago, pianos were built here. Now ten artists plus one kid live and work in the building. Uncle Fred’s one of the artists. Guess who’s the kid?

My skates hobble over the floor’s uneven wooden planks. I like the sound they make. Clickita-clackita, like a train rumbling down the track. I make a quick zig and a zag around some cartons our neighbor Morley has left in the hall. Then I press the elevator button, yank the doors open, and jump over the threshold.

The elevator’s the size of a small room, big enough to hold a piano and an elephant or two. It smells like a mixture of grease, sawdust, and perfume or coffee, depending on who was the last one in.

I pull the door closed and press the button. Next stop: the parking lot. The elevator clunks and screeches as it lowers to the ground. I stare at the sign that’s been here forever. It’s a photograph of a dog with a party hat on. Someone has pasted a speech balloon on the picture and written: “Upon exiting, it would behoove you to close the door!”

This sign has never made sense to me—why not simply say, “Please Close the Door?” But then again, a lot of things don’t make sense when you’re the only kid living in an old piano factory with a bunch of grownups.

The elevator drops to a stop. I open, then close the behooved door. (If you don’t close it all the way, the people upstairs can’t get it to come back up, and they get very upset. Trust me. I know.) I unbolt the door, skate across the concrete loading dock, sit on the edge, and ease myself down to the parking lot.

And groan.

Already I see one dirty diaper, a bag from the donut shop spilling out a squooshed jelly donut and coffee cups, two beer cans, a newspaper, a crumpled bag of chips, and an old shoe. One old shoe? What is that about?

I pull the plastic gloves over my hands and start stuffing a trash bag. The Franklin Piano Factory may look like an abandoned building, with graffiti sprayed across the loading dock and bricks missing in places like a smiling kid with a toothless grin, but people live here. For cripes sake, I live here.

I fill my bag with more trash and hurl it into the dumpster.

Now I can get down to business and start skating. My skate club is holding a skate-a-thon to raise money for our after-school program. If I want to be in it, I have to pass a test. If I want to be in it. Like there’s any question! But I’m no whiz on skates. I’ve got tons of practicing to do.

Before I push off, I glance over to the Piano Factory’s front entrance. Most of the time, the arched opening looks like a mysterious dark keyhole. You can’t see the stone steps worn smooth over time. You can’t see the thick wooden door varnished to a shine. You can’t see the polished brass handle and the list of our neighbors and the round, black buzzers next to their names.

But sometimes, when the sun shines in at the right angle, it lights up that entrance like a small stage.

I have a picture of my mama on just such a day. She’s standing on those front steps, a small woman with a head of spiky black hair. She’s dressed in jeans and a white fuzzy sweater, squinting her eyes in the sun. She’s holding up a baby in a yellow bunny sleeper for the camera.

Me.

Sometimes I look at that keyhole entrance and pretend Mama’s sitting on the steps, hugging her knees to her chest. Watching me.

Ready, Mama? I talk to her in my head. I bend my knees and lean forward. I put weight on the balls of my feet. I suck in a mouthful of air. One, two, ready…. Watch this, Mama! I blow out the air and push off.

Go!

And I’m whizzing through the parking lot. Air whistles through my helmet. I am zooming. Zooooooming!

Of course, I know Mama isn’t watching me. How can she be watching me from the treatment center in Illinois all the way to Haversack, Massachusetts? I know it’s stupid, but I don’t care—I imagine her speaking to me: Way to go, Tillie. Nice work. You’re amazing!

A flock of pigeons swoops down from the factory’s roof, their wings flapping in wild applause. Like Mama herself sent them. I stop and take a bow. Thank you, thank you, pigeons! They settle on the fire escape outside Morley’s pottery studio.

Uh-oh.

I lift the toe of my braking skate and come to a stop. I know what’s coming next. Morley hates those pigeons. She can’t stand their cooing and scratching while she works. Or the mess they leave behind.

I’ll give Morley five seconds. I start counting. One, two, three, four…. Sure enough, the window opens wide. Out she comes with a turquoise bandana tied around her head and clay smudges on her cheeks. She eases herself out the window and stands on the platform. She takes off her striped potter’s apron and shakes it at the pigeons. “Shoo, shoo, shoo! You lousy pigeons,” Morley yells.

The pigeons scratch and flap.

“Hey, Morley,” I call.

“Oh, hi, Tillie. I didn’t see you down there.”

We both watch as the pigeons lift into the air. Right back to their perch on the roof.

“You know they’ll come right back,” says Morley. “Cutie-cat, get out here and do your job.” Morley makes kissing sounds. A gigantic mop of a cat ambles out the window and climbs onto the wooden platform Morley built for him. Morley skritches his head. “How’s the skating going?” she asks me.

“You know that skate club I’m in? We’re holding a fundraiser, a skate-a-thon. I have to take a test if I want to be in it,” I say. I loop around in a wobbly figure eight.

“You? Of course you’ll be in it. I’ve seen you and your friend, what’s her name?”

“Shanelle,” I say.

“…You and your friend Shanelle doing all those tricks,” Morley says.

“Oh, that’s just fooling around. That’s not crossovers and T-stops and….”

“I’m sure you’ll do fine. I have tremendous confidence in you, Ms. Tillie,” Morley says. Then she hooks her apron over her neck, waves, and climbs back through the window.

I wish I had tremendous confidence in me. The truth is, I’m no superstar at much of anything—not softball, not soccer, not schoolwork, not drawing pictures, not piano or dance or gymnastics like other kids in my school. I’m Tillie Watkins. An average, regular, and a-little-on-the-short-side kid.

Uncle Fred says, “What is it about kids these days that they have to have one special thing to shine at?” We act like walking ad campaigns for our extracurricular activities, he says.

There’s a lot Uncle Fred doesn’t understand about kids these days. Like unless you shine at something, you’re invisible.

And I don’t want to be invisible. I want to be a star at something. So I keep skating. Stroking and gliding. Back and forth and across the lot. Soon it’s time to try crossover turns. I set my legs in scissor position, then skate right foot over left. Things are going well. Really well. I’m shifting my weight and keeping my balance. I’m rounding my first corner, when, screeeeaaammm!

A police siren shrieks and wails. My legs wobble. My eyes cross. Darn it, darn it, darn IT!

Don’t flail your arms. Bend at the knees. Touch your knee pads, my coach’s voice comes to me.

But not in time. I tumble to the ground as a police car speeds down the street. Stupid police. Stupid siren.

Stupid me.

I glance up at Uncle Fred’s studio window. Don’t let him be watching. Please don’t let him be watching and run down to check on me. That’s all I need now, Uncle Fred fussing over me, making sure I’m not getting hurt.

Luckily, the window’s empty.

As I roll onto my hands and knees, bring one foot under my body, and push myself to stand, my eyes flit over to the keyhole entrance. That’s okay, baby. Everyone takes a fall now and then, Mama says.

I brush the sand and grit off my jeans. You’re right, Mama, I think. And then you pick yourself up and keep on trying. I get in position to push off and keep circling around the lot.